Is the legal profession truly diverse?

The Black Lives Matter movement sparked a requisite re-evaluation of racial inequality within our society, and despite the numerous amounts of government reviews, there is limited research reviewing and explaining diversity within the legal profession. Hence, this short article aims to discuss diversity within the legal profession in England and Wales; examining and explaining the statistics issued by the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) and the Bar Standards Board (BSB).

Solicitors

Representation

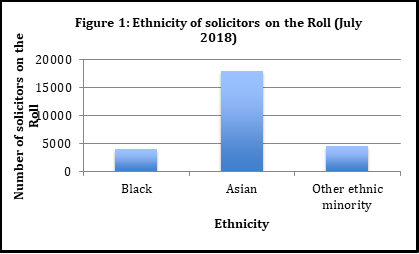

On the face of it, BAME groups seem adequately represented amongst solicitors, although figure 1 demonstrates that this not consistent within differing BAME groups. The statistics show that there is unequal representation amongst Black solicitors, as opposed to Asian solicitors who are strongly represented with 17,932 Asian solicitors on the roll. This can largely be deducted to the cycle of deprivation whereby a poor level of education would act as a barrier to becoming a solicitor. This becomes clear when it is reported that 42% of Indian households bring in a weekly income of £1000 in comparison to 19% of Black households.

Career Progression

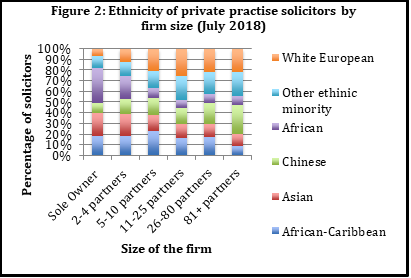

When addressing inequality in respect of career progression, figure 2 provides an insight into the differences amongst differing BAME groups. The key statistic here demonstrates that both, Black (African-Caribbean and African) and Asian solicitors are underrepresented within medium (at +5 partners) and larger firms (at +50 partners). In fact, the Black Solicitors Network (BSN) found that out of 756 magic circle partners, only 5 are Black; revealing an inadequate level of career progression amongst Black and Asian solicitors. In spite of this, it can be noted that that Chinese solicitors have a strong representation within larger firms to the extent it exceeds the number of White European solicitors.

Gender

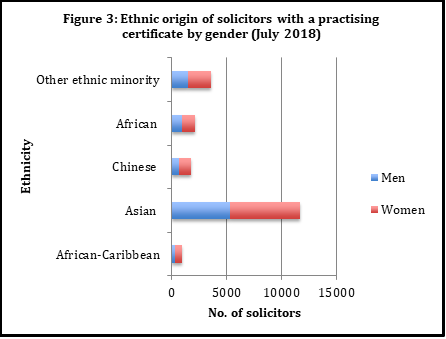

The Law Society Annual Statistics Report 2018 revealed that the number of female solicitors increased to 49% in 2018. Whilst increasing for White European women, figure 3 shows this has increased for all BAME female solicitors to the extent they exceed all BAME male solicitors. All things considered, this marginally scratches the glass ceiling; but this should not be used as a statistic to overshadow the hardships endured by all female solicitors, whether it is career progression or the pay gap.

Barristers

Representation

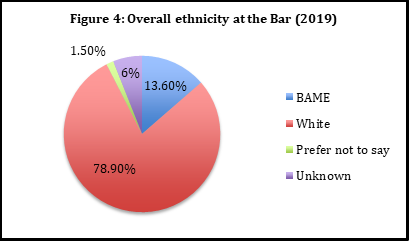

Overall, BAME barristers account for under 1/7th of all 17,367 barristers. When breaking down the overall statistic into differing BAME groups, similar trends that were found amongst BAME solicitors are also somewhat reflective for BAME barristers. For example, Asian barristers are more strongly represented as opposed to their Black peers by 634 more barristers, and mixed peers by 644 more barristers. The social mobility factor also provides a rational reasoning here, as Sam Mercer explains that Russell Group universities are “traditional recruiting ground” for the Bar, and as privately educated students are more likely to attend Russell Group universities, this can explain the discrepancy between White and BAME barristers; especially when 7,285 Asian and 2,740 Black students were accepted into Russell Group universities in 2015 (UCAS). Therefore it can be deduced that social mobility acts as a barrier for BAME representation at the Bar.

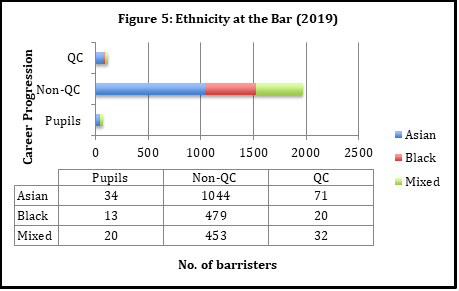

Career Progression

Figure 5 also provides an insight into career progression amongst BAME barristers. Generally, White barristers are dominant in all 3 varying levels of career progression. Beginning with pupils, White pupils account for 79.9% of all pupils compared to 19% of BAME pupils. Although this is a significant improvement when compared to QC barristers, where there are only 8.1% BAME QC barristers. This is generally expected as becoming a QC barrister is achieved through seniority, and thus a consequence of prior inadequate participation rates for BAME barristers a few decades ago.

Gender

Unfortunately the BSB’s statistics are only limited to distinguishing between overall male and female barristers, and fails to provide a breakdown of differing BAME groups. Regardless, this is an issue that needs to be addressed. Unlike the progressive female participation rates for solicitors, for barristers this decreases to 38% for females at the Bar. Though the 12% difference does not entirely seem stark, it is still inadequate. Unfortunately, this statistic fluctuates from year-to-year, whilst in the past the poor participation rates would have unfortunately been due to sexism in the workplace, today it is rather an issue relating to “practical difficulties of being a carer and coping with the vagaries of self-employed, sole practitioner, doing a competitive, stressful and unpredictable job” as explained by QC Pinto.

Strategies to create a diverse workforce within the legal profession

In regards to solicitors, the BSN has devised five action points to be followed by both law firms and legal service providers. This includes creating targets by essentially implementing data collection methods across firms. The second and third action points refer to retention and career progression, suggesting there should be more investment in mentoring schemes to reduce high attrition rates and also investing in BAME talent management to improve career progression. The final two action points shift a focus to the social elements through implementing inclusion training to address organisational culture, whilst also introducing community initiatives to support BAME candidates from unprivileged circumstances.

Efforts within the Bar are currently on-going, and improving gradually; for instance, the Bar Council are attempting to tackle social mobility through initiatives (like the ‘Bar Placement Week’ programme) being offered to year 12 students from unprivileged circumstances. Despite this being an indirect strategy, this does demonstrate that the Bar Council recognises socio-economics as a barrier for Bar pupils and are looking to improve diversity within the profession.

Conclusion

For solicitors, whilst it seems diverse, the solicitor profession is not in fact representative of all BAME groups. For barristers, the profession is not even diverse on the surface and has a similar predicament in that it is not representative of all BAME groups. All in all, it can be said that the legal profession is not wholly diverse and that despite the gradual progressive statistics, there is still a long road ahead in order for the profession to be truly diverse.

Tony S Purewal is an LLB student at the University of Liverpool.

References

1. The Law Society. (2019). Annual Statistics Report 2018 https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/support-services/research-trends/annual-statistics-report-2018/

2. GOV.UK. (2019). Household income https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/work-pay-and-benefits/pay-and-income/household-income/latest

3. Black Solicitors Network. (2020). Seen & Heard. Law Society Gazette (29th June, 13).

4. Bar Standards Board. (2020). Diversity at the Bar 2019 https://www.barstandardsboard.org.uk/uploads/assets/912f7278-48fc-46df-893503eb729598b8/Diversity-at-the-Bar-2019.pdf

5. Russell Group. (2016). University admissions https://russellgroup.ac.uk/news/university-admissions/#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20Mixed%20ethnicity%20students%20accepted%20by%20Russell%20Group,2010%20to%203%2C940%20in%202015.

6. Mercer, S (2015). All Inclusive? 165 The New Law Journal 7647 page 17.

7. Pinto, QC.A. (2019). 100 years of women in the legal profession – some personal reflections from three perspectives. Criminal Law Review 1004.

8. Black Solicitors Network. (2020). BSN’s Open Letter: A call to action for racial diversity. https://www.blacksolicitorsnetwork.co.uk/bsns-open-letter-a-call-to-action-for-racial-diversity/

9. GOV.UK. (2015). Improving Judicial Diversity. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/438207/judicial-diversity-taskforce-annual-report-2014.pdf